Musician, spiritual messenger, and community leader Juan Carlos Sanchez has long promoted Garifuna culture in Labuga, Guatemala, also known as Livingston. In his efforts to increase a general understanding of his community, he has produced an autobiography, Palabra(s) de ounagülei(s), which offers an insider’s perspective on Garifuna life.

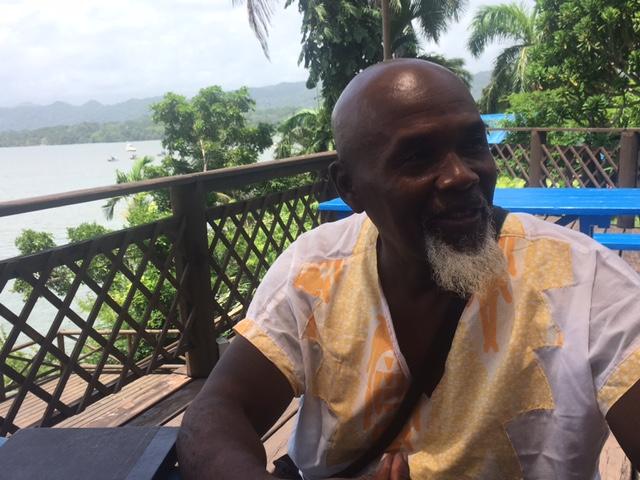

Juan Carlos Sanchez, Livingston, July 16, 2021.

Garifuna populations lie along the Caribbean coastline of Central America, from Belize to Nicaragua. Official data puts the total population at about a quarter million, although some scholars believe the number is significantly greater. Many members of the Garifuna community still speak their own language, which originally formed from Arawak centuries ago, and engage in rituals similar to those their ancestors carried out.

Sanchez discussed his music and the challenges facing his community on July 16, 2021, at a restaurant in a prominent hotel, the Villa Caribe. A popular tourist stopover, the hotel sits on a bluff overlooking the Amatique Bay, where the Rio Dulce (Sweet River) flows into the Caribbean Sea.

Sanchez’s education in music started early and broadened over time. He grew up listening to reggae and calypso music, participated in a punta rock band in the 1980s, and eventually began performing spiritual music in Garifuna ceremonies, becoming a conduit for the ancestors. He also revived a musical genre that was dying out locally, paranda, which today is played in both traditional Garifuna settings and popular venues.

I was raised in the heart of the culture, in its beliefs, customs, and language. Through my music, I have traveled to Europe, the United States, and other parts of Central America, but I continue to live here and have done so my entire life.

Years ago, I realized the youth were not playing paranda (locally), and the people who did were dying off. A gentleman here had become the last of the abuelos to play this music; after him, there would be no one else. (Abuelos means grandparents in Spanish, but he uses the term to describe elder residents and forbears.)

When I saw that this man was sick in 2005, I began to explore and master this style. In May 2006, that man died, but I was ready to continue with the music.

I later went to this hotel, met the manager, and told him I had a project to revive and promote paranda. I wanted to play it to guests because I had played it in the United States, where it was unknown, and people had responded enthusiastically to it. Unfortunately, here in Livingston, people often don’t want what is theirs. They want what is someone else’s.

The manager agreed, so I launched into the world of tourism, performing paranda from 2006 until three years ago. I would go to the hotel’s restaurant or the Dugu Bar in front of it and play every night.

People soon began inviting me to perform in various activities around town, and I played without charging and for whatever occasion. So that’s how I went about rescuing the music.

Juan Carlos Sanchez playing paranda: click to hear. (Found on YouTube)

Paranda is generally played solo, although sometimes other musicians will want to join in. They may get a bottle, a piece of metal, a spoon, or whatever, and begin to mark time, like with a maraca. But generally, it’s just you and a guitar.

Since the idea had awakened within the community and the youth were now playing paranda, I felt I had done my part, so I stopped performing and went back to school. I am not active now, but my music is still in the bar on discs, playing for tourists.

The Dugu Bar at the entrance of the hotel Villa Caribe, where Sanchez once performed to revive paranda. (Photo by Ed Menefee)

The beginnings of paranda can be traced to the early 19th century when the Garifuna exodus to the shores of Central America began. Through the decades, many musical styles have affected its development. Sanchez calls the paranda of today a mixture of soca, blues, and calypso. The style evokes feelings of grief and sorrow from life’s misfortunes, and the lyrics offer a glimpse into the challenges people face in the community.

Garifuna musicians, of course, play several genres, many of which can be heard on the streets of Labuga. While strolling through town, it is common to come across residents drumming and dancing in a traditional style.

There are many musical genres here. Today there is Chumba, there is Punta. All of this is part of Garifuna music. The abuelos used wind instruments, and you still hear some guys using the trumpet as well as the guitar in Garifuna music.

We find, though, that much of the music in Garifuna culture is spiritual. For spiritual ceremonies, the music for all Garifunas is Ugúlendu, and it is performed in Belize, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Guatemala. We play it with two or three drums, using one rhythm with two variations.

There is also a place in spiritual settings for a solo singer, who may sing a ballad. Usually, this person is a messenger who does not imitate anyone else but writes his own songs. He sings about what he sees and experiences. These songs can entail a joke, a story, or be about love, but they are mostly words of advice from the ancestors.

How the musician plays his songs or the rhythm of it is not that relevant in this context. It is what he says that matters, and the people around him will listen and judge whether the performer is spiritual or not.

They chose me to serve in this capacity in 1989. Before that, I wanted to be a great musician, to go to another country and make magnificent music, but the selection of my ancestors kept me away from all of that. I couldn’t be playing in a spiritual ceremony today and a concert tomorrow before 10,000 people. That didn’t make sense to me. So I agreed to follow that call, to serve.

You don’t make much money performing this music. It is not a commercial matter. It isn’t for a concert. It’s there for the people of the community to hear tales about the Garifuna people.

In the traditional Garifuna belief system, spirits of the dead have the ability to communicate with those still living.

The Garifuna form of spirituality is not a religion like Catholicism. We work in a system that contains a variation of Vodou, and we communicate directly with the ancestors. We are talking about the Vodou from Africa, which was intended to make you healthy and protect you. It’s not a Vodou that harms people because they deserve it. It is not done out of hate or revenge. No, it is practiced to provide a barrier between us and those who might harm us, to safeguard the community.

In many rituals, the spirits speak. There are invocations and possessions of the ancestors, who come and talk, while certain members detect if the spirit is authentic.

The ceremonies are well organized and have their leaders and supreme exponents. Everything is structured, and nothing can be done outside of the context of the observance. I worked on it for many years.

We don’t hold any ceremonies that conflict with Catholic celebrations. On Sunday, for instance, there are no ceremonies. We also don’t do anything during Semana Santa between March and April (the Catholic holy week leading to Easter). We are Catholic and respect Catholic laws.

Because of Covid, there have not been any ceremonies this year, because there are routinely 400 to 500 people in one event. That’s a lot of people.

The community also celebrates the more secular holidays throughout the year, such as Settlement Day, which occurs in November. At this time, Garinagu venerate the ancestors for having established the town in the early 1800s, after British troops removed them from their communities on the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent, over a thousand miles away.

It’s beautiful here, and this location (a promontory overlooking the bay) is strategic because you can see anyone who enters. If they are coming from Belize, you can see them, from Honduras and Guatemala also. The ancestors were very intelligent. They inspire me.

The Rio Dulce near the Amatique Bay, Guatemala.

I am a direct descendent of the gentleman who established this town, Marcos Sanchez Díaz; I represent the sixth generation of this person. I feel a responsibility because of it, not because I want to, but because it is in my head. It’s almost telepathic. My forefathers were leaders here. My grandfather was the mayor in 1954 and led the community. I try to educate myself to continue with the ideals of my grandparents and their grandparents.

When I feel like I no longer have a solution to a problem, a solution of my own, I receive my ancestors’ indications. It is in a dream that they guide me. Yes, there is that connection. It exists.

***

Sanchez grew up just north of the center of Livingston in a village called La Guaira, where he would go with his grandparents up a mountain, plant corn, rice, and yucca, and bring back timber. In his memoir, Sanchez recalled walking along the seashore and seeing canoes gliding toward town carrying produce like plantains, oranges, cassavas, cacao, grapefruit, sugar cane, and bananas. The area’s natural abundance affords opportunities to plant crops, grow fruit trees, and fish, providing residents with sustenance and a distinct cuisine.

Nutrition is central to the traditional Garifuna diet. Foods are often eaten together, like fish and coconut. Bananas were commonly used and still are because you can make different dishes with the banana — be they grated, grilled, fried, or roasted. You can also make a tamale or a type of cake with them.

Drinks in the past were made from various fruits, like lime or lemon, orange, grapefruit, or pineapple. The ancestors also knew how to make their drinks with yucca, sometimes grated, squeezed, or burned, like in a burnt cake. Then they added water with grated sweet potato.

All the Garifuna food that I have seen is to keep you healthy.

More commercially popular foods like spaghetti and fast food are now eaten in addition, but what you eat depends on your health. We are not eating the same thing every day. You have to balance what you eat.

***

Economic and demographic changes, of course, have had their effect on Garifuna culture. Sánchez believes that an influx of outside groups into Labuga has posed a challenge to the community’s unity and traditions, as has the exodus of its own residents to find work in locations like the Guatemalan capital or the United States.

The decline in the use of the Garifuna language is especially troubling.

There are now many different cultures here: mestizos, indigenous Mayas, Hindu people, some Chinese and Japanese. Because there are so many groups coming in, we have to speak Spanish with them, so we are speaking Garifuna less and less.

About 50 years ago, everything was in Garifuna. Now our language is scarcely spoken in the street. The children instead speak Spanish, which is the language in school, on television, and on the radio. Almost everything is in Spanish. I have friends who don’t speak Garifuna, yet they are Garifuna. Sadly, many people want to imitate others or feel superior to others, so they leave parts of their own culture behind.

When I was a child, at home, if someone mentioned a word in Spanish, we would laugh, as if listening to a clown, because the language was so foreign. You only heard Garifuna. I learned Spanish in school because that is what the teachers understood, so we had to speak it.

The Garifuna language is essential because it reflects and keeps our culture alive. For instance, we use the word “judutu,” which means to cook, but the term we use implies that a lot of preparation and work has gone into the cooking. When we hear “judutu,” we know that it results from a long process.

To give you another example, in Spanish, it is common to say good morning, “Buenos días,” and in Garifuna, we would translate that literally as “Buiti binafi.” But that expression doesn’t exist in our language. We use a different phrase, which is used to see how you are. It’s “Idabiña.” Everybody is asked how they are when greeted. You don’t say to someone, “Hola, buenos días,” and leave. Or “Hola buenos días, adios.” Not in Garifuna. It’s “Idabiña.” And afterwards I stop to listen to you and begin to speak with you to see if you are OK. So, many matters are represented in the language that help our culture maintain its essence, as well as our connection to other Garifuna communities.

***

Sanchez’s perspective on his community has been shaped not only by his role as a musician and spiritual leader but also by his work in social services, which he has carried out for over 25 years.

I currently work for the government, training and consulting on issues of violence, sexual violence, exploitation, and human trafficking. This year the work ended due to the pandemic. Now, I just get small jobs here and there.

Violence is living with us, between us, including in our homes, and it’s difficult to eradicate.

Violence is a type of inheritance that is generated constantly, and there are many forms of it. Violence has existed since the beginning of humanity. Remember that to eat, people had to kill an animal. And still, up until today, to eat “un caldo de pollo,” chicken soup, you have to kill a chicken. Is that violence, or is it not? Yes, it’s violence because you are killing.

Even in mining, to make a hole in the ground, there are stones to break apart, and you have to use a lot of heavy energy to do it, which is violent. Violence is done to the environment. (A nickel mine lies downriver on Lake Izabal, affecting many residents nearby.) I am not against mining, but many people suffer from it and are left without safe water or animals. Some can adapt while others suffer.

So violence takes place not just at home. It’s everywhere.

***

Sanchez sees education, in particular, as vital to dealing with a range of social challenges. In Guatemala, national spending on education is, unfortunately, one of the lowest in the world as a percentage of GDP. Schools in marginalized communities like the Garifuna often lack educational materials, like textbooks, and are beset by deteriorating infrastructure, affecting the supply of water and electricity. The pool of talented educators is also limited due to low teacher pay and Labuga’s lengthy distance from larger, urban areas where most teachers are trained.

Adding to the problem, residents from poorer communities frequently lack the personal funds to keep their children in school. The costs of uniforms, books, supplies, and transportation, none of which the state supplies, often prevent students from continuing their education. Guatemalan children commonly stop their studies at the age of 12, the transition between primary and secondary level schools, hoping instead to work and make money for their families. Ironically, the quest for financial stability tends to limit the value placed on education.

Sanchez himself graduated from high school in Livingston and years later, in 2016, began studying for his bachelor’s degree at a university (Santo Tomás) near Puerto Barrios.

Education is not well promoted in our community. There is very little effort to make people understand that education is important, and the people are not at fault. It is the fault of the government.

Some with influence benefit from keeping others from reading and writing, and a president can say that he wants education for the Garifuna people, but he can’t do anything alone. Others can say no. All 150 deputies in Congress, who are representing various interests, have sway over what the president does.

It all has to do with the land. The land is what produces, especially primary materials to export. If there are people who don’t know how to read or write, they can be paid very little to work the land, because they don’t know their rights. That’s why their education is not supported adequately in some sectors. If we were autonomous, if we had our own territory, we could probably change that, but we do not have a territory. All we have are individual pieces of land —— and we can’t legislate.

What is needed for autonomy, though, is a lot of brains, and if there are insufficient levels of education among the people, you are not going to be able to have autonomy. It can be given to you but it’s only going to be a failure.

Low levels of education also make it difficult for residents to defend their property from encroachment, which has become common in Garifuna communities. Through improper development, the Garinugas may gradually lose their ability to inhabit their own land along the coast, with its beautiful beaches, warm water, and natural beauty.

In Honduras, where the Garifuna population is largest, community activists have been kidnapped and killed trying to protect local territory. Among those vying for Garifuna land are foreign hotel companies, drug cartels aiming to use the space to transport drugs, and Palm Oil companies hoping to expand their plantations.

Garifuna homeowner (left) enjoying his ocean-front property, Livingston, Guatemala.

While Labuga has avoided the violence seen in Honduras, it could face similar dangers in the future. Lying between two large bodies of water, the town remains attractive to outsiders. The Guatemalan government, for its part, encourages foreign-sponsored development to increase tourism and foreign exchange, but future development could squeeze out residents and jeopardize the private and public spaces members of the community enjoy.

Hotel Villa Caribe, Livingston, Guatemala.

Look at this hotel. Many years ago, we would walk here and no one would say that this land was theirs. But the government knew that this could be a place that could be exploited. They let people live here to clean and prepare the place, but when it was cleared and ready, various interests put up their restaurants and hotels.

It isn’t that the Guatemalan government is bad or worse, and so are doing that. No, this has been done for many years in other countries and cities, and Guatemala has followed that model. That is an old practice.

But now you cannot go through here.

Land along the Labuga coastline, now owned by a hotel and restaurant.

The above narrative, taken from an interview I conducted in Livingston on July 16, 2021, represents my translation and edits. For more on Juan Carlos Sánchez, consult his book, Palabra(s) de ounagülei(s): La espiritualidad garífuna de Livingston, Guatemala, Un texto de Juan Carlos Sánchez, compilado y editado por Augusto Pérez Guarnieri (Guatemala: Flacso Guatemala, 2018).

For an excellent compilation of paranda music, see “Paranda – Africa in Central America,” which features artists Paul Neybor, Jursino Cayetano, Aurelio Martinez, Lugua Centeno, and Andy Palacio. The album can be found on YouTube.